AUTHORS:

This is a straightforward binding to the MPFI library; it may be useful to refer to its documentation for more details.

An interval is represented as a pair of floating-point numbers a and b (where a <= b) and is printed as a standard floating-point number with a question mark (for instance, 3.1416?). The question mark indicates that the preceding digit may have an error of +/- 1. These floating-point numbers are implemented using MPFR (the same as the RealNumber elements of RealField).

There is also an alternate method of printing, where the interval prints as [a .. b] (for instance, [3.1415 .. 3.1416]).

The interval represents the set { x : a <= x <= b } (so if a == b, then the interval represents that particular floating-point number). The endpoints can include positive and negative infinity, with the obvious meaning. It is also possible to have a NaN (not-a-number) interval, which is represented by having either endpoint be NaN.

PRINTING:

There are two styles for printing intervals: ‘brackets’ style and ‘question’ style (the default).

In question style, we print the “known correct” part of the number, followed by a question mark. The question mark indicates that the preceding digit is possibly wrong by +/- 1.

sage: RIF(sqrt(2))

1.414213562373095?

However, if the interval is precise (its lower bound is equal to its upper bound) and equal to a not-too-large integer, then we just print that integer.

sage: RIF(0)

0

sage: RIF(654321)

654321

sage: RIF(123, 125)

124.?

sage: RIF(123, 126)

1.3?e2

As we see in the last example, question style can discard almost a whole digit’s worth of precision. We can reduce this by allowing “error digits”: an error following the question mark, that gives the maximum error of the digit(s) before the question mark. If the error is absent (which it always is in the default printing), then it is taken to be 1.

sage: RIF(123, 126).str(error_digits=1)

'125.?2'

sage: RIF(123, 127).str(error_digits=1)

'125.?2'

sage: v = RIF(-e, pi); v

0.?e1

sage: v.str(error_digits=1)

'1.?4'

sage: v.str(error_digits=5)

'0.2117?29300'

Error digits also sometimes let us indicate that the interval is actually equal to a single floating-point number.

sage: RIF(54321/256)

212.19140625000000?

sage: RIF(54321/256).str(error_digits=1)

'212.19140625000000?0'

In brackets style, intervals are printed with the left value rounded down and the right rounded up, which is conservative, but in some ways unsatisfying.

Consider a 3-bit interval containing exactly the floating-point number 1.25. In round-to-nearest or round-down, this prints as 1.2; in round-up, this prints as 1.3. The straightforward options, then, are to print this interval as [1.2 .. 1.2] (which does not even contain the true value, 1.25), or to print it as [1.2 .. 1.3] (which gives the impression that the upper and lower bounds are not equal, even though they really are). Neither of these is very satisfying, but we have chosen the latter.

sage: R = RealIntervalField(3)

sage: a = R(1.25)

sage: a.str(style='brackets')

'[1.2 .. 1.3]'

sage: a == 1.25

True

sage: a == 2

False

COMPARISONS:

Comparison operations (==,!=,<,<=,>,>=) return true if every value in the first interval has the given relation to every value in the second interval. The cmp(a, b) function works differently; it compares two intervals lexicographically. (However, the behavior is not specified if given a non-interval and an interval.)

This convention for comparison operators has good and bad points. The good:

The bad:

Note that intervals a and b overlap iff not(a != b).

EXAMPLES:

sage: 0 < RIF(1, 2)

True

sage: 0 == RIF(0)

True

sage: not(0 == RIF(0, 1))

True

sage: not(0 != RIF(0, 1))

True

sage: 0 <= RIF(0, 1)

True

sage: not(0 < RIF(0, 1))

True

sage: cmp(RIF(0), RIF(0, 1))

-1

sage: cmp(RIF(0, 1), RIF(0))

1

sage: cmp(RIF(0, 1), RIF(1))

-1

sage: cmp(RIF(0, 1), RIF(0, 1))

0

Return the real number defined by the string s as an element of RealIntervalField(prec=n), where n potentially has slightly more (controlled by pad) bits than given by s.

INPUT:

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealInterval('2.3')

2.300000000000000?

sage: RealInterval(10)

10

sage: RealInterval('1.0000000000000000000000000000000000')

1

sage: RealInterval('1.2345678901234567890123456789012345')

1.23456789012345678901234567890123450?

sage: RealInterval(29308290382930840239842390482, 3^20).str(style='brackets')

'[3.48678440100000000000000000000e9 .. 2.93082903829308402398423904820e28]'

Construct a RealIntervalField_class, with caching.

INPUT:

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField()

Real Interval Field with 53 bits of precision

sage: RealIntervalField(200, sci_not=True)

Real Interval Field with 200 bits of precision

sage: RealIntervalField(53) is RIF

True

sage: RealIntervalField(200) is RIF

False

sage: RealIntervalField(200) is RealIntervalField(200)

True

See the documentation for RealIntervalField_class for many more examples.

Bases: sage.structure.element.RingElement

A real number interval.

The diameter of this interval (for [a .. b], this is b-a), rounded upward, as a RealNumber.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, pi).absolute_diameter()

2.14159265358979

RIF(a, b).alea() gives a floating-point number picked at random from the interval.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).alea() # random

1.34696133696137

Returns a polynomial of degree at most  which is

approximately satisfied by this number. Note that the returned

polynomial need not be irreducible, and indeed usually won’t be if

this number is a good approximation to an algebraic number of

degree less than

which is

approximately satisfied by this number. Note that the returned

polynomial need not be irreducible, and indeed usually won’t be if

this number is a good approximation to an algebraic number of

degree less than  .

.

Pari needs to know the number of “known good bits” in the number; we automatically get that from the interval width.

ALGORITHM: Uses the PARI C-library algdep command.

EXAMPLE:

sage: r = sqrt(RIF(2)); r

1.414213562373095?

sage: r.algdep(5)

x^2 - 2

If we compute a wrong, but precise, interval, we get a wrong answer.

sage: r = sqrt(RealIntervalField(200)(2)) + (1/2)^40; r

1.414213562374004543503461652447613117632171875376948073176680?

sage: r.algdep(5)

7266488*x^5 + 22441629*x^4 - 90470501*x^3 + 23297703*x^2 + 45778664*x + 13681026

But if we compute an interval that includes the number we mean, we’re much more likely to get the right answer, even if the interval is very imprecise.

sage: r = r.union(sqrt(2.0))

sage: r.algdep(5)

x^2 - 2

Even on this extremely imprecise interval we get an answer which is technically correct.

sage: RIF(-1, 1).algdep(5)

x

Returns the inverse cosine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/3; q

1.047197551196598?

sage: i = q.cos(); i

0.500000000000000?

sage: q2 = i.arccos(); q2

1.047197551196598?

sage: q == q2

False

sage: q != q2

False

sage: q2.lower() == q.lower()

False

sage: q - q2

0.?e-15

sage: q in q2

True

Returns the hyperbolic inverse cosine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/2

sage: i = q.arccosh() ; i

1.023227478547551?

Returns the inverse hyperbolic cotangent of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).arccoth()

0.549306144334054845697622618462?

sage: (2.0).arccoth()

0.549306144334055

Returns the inverse hyperbolic cosecant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).arccsch()

0.481211825059603447497758913425?

sage: (2.0).arccsch()

0.481211825059603

Returns the inverse hyperbolic secant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(0.5).arcsech()

1.316957896924816708625046347308?

sage: (0.5).arcsech()

1.31695789692482

Returns the inverse sine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/5; q

0.6283185307179587?

sage: i = q.sin(); i

0.587785252292474?

sage: q2 = i.arcsin(); q2

0.628318530717959?

sage: q == q2

False

sage: q != q2

False

sage: q2.lower() == q.lower()

False

sage: q - q2

0.?e-15

sage: q in q2

True

Returns the hyperbolic inverse sine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/7

sage: i = q.sinh() ; i

0.464017630492991?

sage: i.arcsinh() - q

0.?e-15

Returns the inverse tangent of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/5; q

0.6283185307179587?

sage: i = q.tan(); i

0.726542528005361?

sage: q2 = i.arctan(); q2

0.628318530717959?

sage: q == q2

False

sage: q != q2

False

sage: q2.lower() == q.lower()

False

sage: q - q2

0.?e-15

sage: q in q2

True

Returns the hyperbolic inverse tangent of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/7

sage: i = q.tanh() ; i

0.420911241048535?

sage: i.arctanh() - q

0.?e-15

Returns the ceiling of this number

OUTPUT: integer

EXAMPLES:

sage: (2.99).ceil()

3

sage: (2.00).ceil()

2

sage: (2.01).ceil()

3

sage: R = RealIntervalField(30)

sage: a = R(-9.5, -11.3); a.str(style='brackets')

'[-11.300000012 .. -9.5000000000]'

sage: a.floor().str(style='brackets')

'[-12.000000000 .. -10.000000000]'

sage: a.ceil()

-10.?

sage: ceil(a).str(style='brackets')

'[-11.000000000 .. -9.0000000000]'

RIF(a, b).center() == (a+b)/2

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).center()

1.50000000000000

Returns True if self is an interval containing zero.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(0).contains_zero()

True

sage: RIF(1, 2).contains_zero()

False

sage: RIF(-1, 1).contains_zero()

True

sage: RIF(-1, 0).contains_zero()

True

Returns the cosine of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: t=RIF(pi)/2

sage: t.cos()

0.?e-15

sage: t.cos().str(style='brackets')

'[-1.6081226496766367e-16 .. 6.1232339957367661e-17]'

sage: t.cos().cos()

0.9999999999999999?

TESTS:

This looped forever with an earlier version of MPFI, but now it works.

sage: RIF(-1, 1).cos().str(style='brackets')

'[0.54030230586813965 .. 1.0000000000000000]'

Returns the hyperbolic cosine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/12

sage: q.cosh()

1.034465640095511?

Returns the cotangent of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).cot()

-0.457657554360285763750277410432?

Returns the hyperbolic cotangent of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).coth()

1.03731472072754809587780976477?

Returns the cosecant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).csc()

1.099750170294616466756697397026?

Returns the hyperbolic cosecant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).csch()

0.275720564771783207758351482163?

If (0 in self), returns self.absolute_diameter(), otherwise self.relative_diameter().

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).diameter()

0.666666666666667

sage: RIF(1, 2).absolute_diameter()

1.00000000000000

sage: RIF(1, 2).relative_diameter()

0.666666666666667

sage: RIF(pi).diameter()

1.41357985842823e-16

sage: RIF(pi).absolute_diameter()

4.44089209850063e-16

sage: RIF(pi).relative_diameter()

1.41357985842823e-16

sage: (RIF(pi) - RIF(3, 22/7)).diameter()

0.142857142857144

sage: (RIF(pi) - RIF(3, 22/7)).absolute_diameter()

0.142857142857144

sage: (RIF(pi) - RIF(3, 22/7)).relative_diameter()

2.03604377705518

Returns

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(0.0)

sage: r.exp()

1

sage: r = RIF(32.3)

sage: a = r.exp(); a

1.065888472748645?e14

sage: a.log()

32.30000000000000?

sage: r = RIF(-32.3)

sage: r.exp()

9.38184458849869?e-15

Returns

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(0.0)

sage: r.exp2()

1

sage: r = RIF(32.0)

sage: r.exp2()

4294967296

sage: r = RIF(-32.3)

sage: r.exp2()

1.891172482530207?e-10

Returns the floor of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField()

sage: (2.99).floor()

2

sage: (2.00).floor()

2

sage: floor(RR(-5/2))

-3

sage: R = RealIntervalField(100)

sage: a = R(9.5, 11.3); a.str(style='brackets')

'[9.5000000000000000000000000000000 .. 11.300000000000000710542735760101]'

sage: floor(a).str(style='brackets')

'[9.0000000000000000000000000000000 .. 11.000000000000000000000000000000]'

sage: a.floor()

10.?

sage: ceil(a)

11.?

sage: a.ceil().str(style='brackets')

'[10.000000000000000000000000000000 .. 12.000000000000000000000000000000]'

Computes the diameter of this interval in terms of the “floating-point rank”. That is, it gives the number of floating-point numbers (of the current precision) contained in the given interval, minus one. An fp_rank_diameter of 0 means that the interval is exact; an fp_rank_diameter of 1 means that the interval is as tight as possible, unless the number you’re trying to represent is actually exactly representable as a floating-point number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(pi).fp_rank_diameter()

1

sage: RIF(12345).fp_rank_diameter()

0

sage: RIF(-sqrt(2)).fp_rank_diameter()

1

sage: RIF(5/8).fp_rank_diameter()

0

sage: RIF(5/7).fp_rank_diameter()

1

sage: a = RIF(pi)^12345; a

2.06622879260?e6137

sage: a.fp_rank_diameter()

30524

sage: (RIF(sqrt(2)) - RIF(sqrt(2))).fp_rank_diameter()

9671406088542672151117826

Just because we have the best possible interval, doesn’t mean the interval is actually small:

sage: a = RIF(pi)^1234567890; a

[2.0985787164673874e323228496 .. +infinity]

sage: a.fp_rank_diameter()

1

Return the intersection of two intervals. If the intervals do not overlap, raises a ValueError.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).intersection(RIF(1.5, 3)).str(style='brackets')

'[1.5000000000000000 .. 2.0000000000000000]'

sage: RIF(1, 2).intersection(RIF(4/3, 5/3)).str(style='brackets')

'[1.3333333333333332 .. 1.6666666666666668]'

sage: RIF(1, 2).intersection(RIF(3, 4))

...

ValueError: intersection of non-overlapping intervals

OUTPUT:

Checks to see whether this interval includes exactly one integer. If so, returns a tuple (True, n), where n is that integer; otherwise, returns (False, None).

EXAMPLES:

sage: a = RIF(0.8,1.5)

sage: a.is_int()

(True, 1)

sage: a = RIF(1.1,1.5)

sage: a.is_int()

(False, None)

sage: a = RIF(1,2)

sage: a.is_int()

(False, None)

sage: a = RIF(-1.1, -0.9)

sage: a.is_int()

(True, -1)

sage: a = RIF(0.1, 1.9)

sage: a.is_int()

(True, 1)

sage: RIF(+infinity,+infinity).is_int()

(False, None)

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField()

sage: r = R(2); r.log()

0.6931471805599453?

sage: r = R(-2); r.log()

0.6931471805599453? + 3.141592653589794?*I

Returns log to the base 10 of self

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(16.0); r.log10()

1.204119982655925?

sage: r.log() / log(10.0)

1.204119982655925?

sage: r = RIF(39.9); r.log10()

1.600972895686749?

sage: r = RIF(0.0)

sage: r.log10()

[-infinity .. -infinity]

sage: r = RIF(-1.0)

sage: r.log10()

1.364376353841841?*I

Returns log to the base 2 of self

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(16.0)

sage: r.log2()

4

sage: r = RIF(31.9); r.log2()

4.995484518877507?

sage: r = RIF(0.0, 2.0)

sage: r.log2()

[-infinity .. 1.0000000000000000]

Returns the lower bound of this interval

rnd - (string) the rounding mode

The rounding mode does not affect the value returned as a floating-point number, but it does control which variety of RealField the returned number is in, which affects printing and subsequent operations.

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(13)

sage: R.pi().lower().str(truncate=False)

'3.1411'

sage: x = R(1.2,1.3); x.str(style='brackets')

'[1.1999 .. 1.3001]'

sage: x.lower()

1.19

sage: x.lower('RNDU')

1.20

sage: x.lower('RNDN')

1.20

sage: x.lower('RNDZ')

1.19

sage: x.lower().parent()

Real Field with 13 bits of precision and rounding RNDD

sage: x.lower('RNDU').parent()

Real Field with 13 bits of precision and rounding RNDU

sage: x.lower() == x.lower('RNDU')

True

The largest absolute value of the elements of the interval.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(-2, 1).magnitude()

2.00000000000000

sage: RIF(-1, 2).magnitude()

2.00000000000000

The smallest absolute value of the elements of the interval.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(-2, 1).mignitude()

0.000000000000000

sage: RIF(-2, -1).mignitude()

1.00000000000000

sage: RIF(3, 4).mignitude()

3.00000000000000

Returns true if self and other are intervals with at least one value in common. For intervals a and b, we have a.overlaps(b) iff not(a!=b).

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(0, 1).overlaps(RIF(1, 2))

True

sage: RIF(1, 2).overlaps(RIF(0, 1))

True

sage: RIF(0, 1).overlaps(RIF(2, 3))

False

sage: RIF(2, 3).overlaps(RIF(0, 1))

False

sage: RIF(0, 3).overlaps(RIF(1, 2))

True

sage: RIF(0, 2).overlaps(RIF(1, 3))

True

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField()

sage: a = R('1.2456')

sage: a.parent()

Real Interval Field with 53 bits of precision

Return the real part of self.

(Since self is a real number, this simply returns self.)

The relative diameter of this interval (for [a .. b], this is (b-a)/((a+b)/2)), rounded upward, as a RealNumber.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, pi).relative_diameter()

1.03418797197910

Returns the secant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).sec()

-2.40299796172238098975460040142?

Returns the hyperbolic secant of this number.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100)(2).sech()

0.265802228834079692120862739820?

Returns the simplest rational in this interval. Given rationals a/b

and c/d (both in lowest terms), the former is simpler if b<d or if

b==d and  .

.

If optional parameters low_open or high_open are true, then treat this as an open interval on that end.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(10)(pi).simplest_rational()

22/7

sage: RealIntervalField(20)(pi).simplest_rational()

355/113

sage: RIF(0.123, 0.567).simplest_rational()

1/2

sage: RIF(RR(1/3).nextabove(), RR(3/7)).simplest_rational()

2/5

sage: RIF(1234/567).simplest_rational()

1234/567

sage: RIF(-8765/432).simplest_rational()

-8765/432

sage: RIF(-1.234, 0.003).simplest_rational()

0

sage: RIF(RR(1/3)).simplest_rational()

6004799503160661/18014398509481984

sage: RIF(RR(1/3)).simplest_rational(high_open=True)

...

ValueError: simplest_rational() on open, empty interval

sage: RIF(1/3, 1/2).simplest_rational()

1/2

sage: RIF(1/3, 1/2).simplest_rational(high_open=True)

1/3

sage: phi = ((RealIntervalField(500)(5).sqrt() + 1)/2)

sage: phi.simplest_rational() == fibonacci(362)/fibonacci(361)

True

Returns the sine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(100)

sage: R(2).sin()

0.909297426825681695396019865912?

Returns the hyperbolic sine of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/12

sage: q.sinh()

0.2648002276022707?

Return a square root of self. Raises an error if self is nonpositive.

If you use self.square_root() then an interval will always be returned (though it will be NaN if self is nonpositive).

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(4.0)

sage: r.sqrt()

2

sage: r.sqrt()^2 == r

True

sage: r = RIF(4344)

sage: r.sqrt()

65.90902821313633?

sage: r.sqrt()^2 == r

False

sage: r in r.sqrt()^2

True

sage: r.sqrt()^2 - r

0.?e-11

sage: (r.sqrt()^2 - r).str(style='brackets')

'[-9.0949470177292824e-13 .. 1.8189894035458565e-12]'

sage: r = RIF(-2.0)

sage: r.sqrt()

...

ValueError: self (=-2) is not >= 0

sage: r = RIF(-2, 2)

sage: r.sqrt()

...

ValueError: self (=0.?e1) is not >= 0

Return the square of the interval. Note that squaring an interval is different than multiplying it by itself, because the square can never be negative.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).square().str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 4.0000000000000000]'

sage: RIF(-1, 1).square().str(style='brackets')

'[0.00000000000000000 .. 1.0000000000000000]'

sage: (RIF(-1, 1) * RIF(-1, 1)).str(style='brackets')

'[-1.0000000000000000 .. 1.0000000000000000]'

Return a square root of self. An interval will always be returned (though it will be NaN if self is nonpositive).

EXAMPLES:

sage: r = RIF(-2.0)

sage: r.square_root()

[.. NaN ..]

sage: r.sqrt()

...

ValueError: self (=-2) is not >= 0

INPUT:

We support two different styles of printing; ‘question’ style and ‘brackets’ style. In question style (the default), we print the “known correct” part of the number, followed by a question mark:

sage: RIF(pi).str()

'3.141592653589794?'

sage: RIF(pi, 22/7).str()

'3.142?'

sage: RIF(pi, 22/7).str(style='question')

'3.142?'

However, if the interval is precisely equal to some integer that’s not too large, we just return that integer.

sage: RIF(-42).str()

'-42'

sage: RIF(0).str()

'0'

sage: RIF(12^5).str(base=3)

'110122100000'

Very large integers, however, revert to the normal question-style printing.

sage: RIF(3^7).str()

'2187'

sage: RIF(3^7 * 2^256).str()

'2.5323729916201052?e80'

In brackets style, we print the lower and upper bounds of the interval within brackets:

sage: RIF(237/16).str(style='brackets')

'[14.812500000000000 .. 14.812500000000000]'

Note that the lower bound is rounded down, and the upper bound is rounded up. So even if the lower and upper bounds are equal, they may print differently. (This is done so that the printed representation of the interval contains all the numbers in the internal binary interval.)

For instance, we find the best 10-bit floating point representation of 1/3:

sage: RR10 = RealField(10)

sage: RR(RR10(1/3))

0.333496093750000

And we see that the point interval containing only this floating-point number prints as a wider decimal interval, that does contain the number:

sage: RIF10 = RealIntervalField(10)

sage: RIF10(RR10(1/3)).str(style='brackets')

'[0.33349 .. 0.33350]'

We always use brackets style for NaN and infinities.

sage: RIF(pi, infinity)

[3.1415926535897931 .. +infinity]

sage: RIF(NaN)

[.. NaN ..]

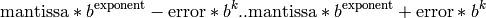

Let’s take a closer, formal look at the question style. In its full generality, a number printed in the question style looks like:

MANTISSA ?ERROR eEXPONENT

(without the spaces). The “eEXPONENT” part is optional; if it is missing, then the exponent is 0. (If the base is greater than 10, then the exponent separator is “@” instead of “e”.)

The “ERROR” is optional; if it is missing, then the error is 1.

The mantissa is printed in base  , and always contains a

decimal point (also known as a radix point, in bases other than

10). (The error and exponent are always printed in base 10.)

, and always contains a

decimal point (also known as a radix point, in bases other than

10). (The error and exponent are always printed in base 10.)

We define the “precision” of a floating-point printed

representation to be the positional value of the last digit of the

mantissa. For instance, in 2.7?e5, the precision is  ;

in 8.?, the precision is

;

in 8.?, the precision is  ; and in 9.35? the precision

is

; and in 9.35? the precision

is  . This precision will always be

. This precision will always be  for some

for some  (or, for an arbitrary base

(or, for an arbitrary base  ,

,

).

).

Then the interval is contained in the interval:

To control the printing, we can specify a maximum number of error digits. The default is 0, which means that we do not print an error at all (so that the error is always the default, 1).

Now, consider the precisions needed to represent the endpoints (this is the precision that would be produced by v.lower().str(no_sci=False, truncate=False)). Our result is no more precise than the less precise endpoint, and is sufficiently imprecise that the error can be represented with the given number of decimal digits. Our result is the most precise possible result, given these restrictions. When there are two possible results of equal precision and with the same error width, then we pick the one which is farther from zero. (For instance, RIF(0, 123) with two error digits could print as 61.?62 or 62.?62. We prefer the latter because it makes it clear that the interval is known not to be negative.)

EXAMPLES:

sage: a = RIF(59/27); a

2.185185185185186?

sage: a.str()

'2.185185185185186?'

sage: a.str(style='brackets')

'[2.1851851851851851 .. 2.1851851851851856]'

sage: a.str(16)

'2.2f684bda12f69?'

sage: a.str(no_sci=False)

'2.185185185185186?e0'

sage: pi_appr = RIF(pi, 22/7)

sage: pi_appr.str(style='brackets')

'[3.1415926535897931 .. 3.1428571428571433]'

sage: pi_appr.str()

'3.142?'

sage: pi_appr.str(error_digits=1)

'3.1422?7'

sage: pi_appr.str(error_digits=2)

'3.14223?64'

sage: pi_appr.str(base=36)

'3.6?'

sage: RIF(NaN)

[.. NaN ..]

sage: RIF(pi, infinity)

[3.1415926535897931 .. +infinity]

sage: RIF(-infinity, pi)

[-infinity .. 3.1415926535897936]

sage: RealIntervalField(210)(3).sqrt()

1.732050807568877293527446341505872366942805253810380628055806980?

sage: RealIntervalField(210)(RIF(3).sqrt())

1.732050807568878?

sage: RIF(3).sqrt()

1.732050807568878?

sage: RIF(0, 3^-150)

1.?e-71

Returns the tangent of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/3

sage: q.tan()

1.732050807568877?

sage: q = RIF.pi()/6

sage: q.tan()

0.577350269189626?

Returns the hyperbolic tangent of this number

EXAMPLES:

sage: q = RIF.pi()/11

sage: q.tanh()

0.2780794292958503?

Return the union of two intervals, or of an interval and a real number (more precisely, the convex hull).

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF(1, 2).union(RIF(pi, 22/7)).str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 3.1428571428571433]'

sage: RIF(1, 2).union(pi).str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 3.1415926535897936]'

sage: RIF(1).union(RIF(0, 2)).str(style='brackets')

'[0.00000000000000000 .. 2.0000000000000000]'

sage: RIF(1).union(RIF(-1)).str(style='brackets')

'[-1.0000000000000000 .. 1.0000000000000000]'

Returns the upper bound of this interval

The rounding mode does not affect the value returned as a floating-point number, but it does control which variety of RealField the returned number is in, which affects printing and subsequent operations.

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(13)

sage: R.pi().upper().str(truncate=False)

'3.1417'

sage: R = RealIntervalField(13)

sage: x = R(1.2,1.3); x.str(style='brackets')

'[1.1999 .. 1.3001]'

sage: x.upper()

1.31

sage: x.upper('RNDU')

1.31

sage: x.upper('RNDN')

1.30

sage: x.upper('RNDD')

1.30

sage: x.upper('RNDZ')

1.30

sage: x.upper().parent()

Real Field with 13 bits of precision and rounding RNDU

sage: x.upper('RNDD').parent()

Real Field with 13 bits of precision and rounding RNDD

sage: x.upper() == x.upper('RNDD')

True

Bases: sage.rings.ring.Field

RealIntervalField(prec, sci_not):

INPUT:

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(10)

Real Interval Field with 10 bits of precision

sage: RealIntervalField()

Real Interval Field with 53 bits of precision

sage: RealIntervalField(100000)

Real Interval Field with 100000 bits of precision

Note

The default precision is 53, since according to the GMP manual: ‘mpfr should be able to exactly reproduce all computations with double-precision machine floating-point numbers (double type in C), except the default exponent range is much wider and subnormal numbers are not implemented.’

EXAMPLES: Creation of elements

First with default precision. First we coerce elements of various types, then we coerce intervals.

sage: RIF = RealIntervalField(); RIF

Real Interval Field with 53 bits of precision

sage: RIF(3)

3

sage: RIF(RIF(3))

3

sage: RIF(pi)

3.141592653589794?

sage: RIF(RealField(53)('1.5'))

1.5000000000000000?

sage: RIF(-2/19)

-0.1052631578947369?

sage: RIF(-3939)

-3939

sage: RIF(-3939r)

-3939

sage: RIF('1.5')

1.5000000000000000?

sage: R200 = RealField(200)

sage: RIF(R200.pi())

3.141592653589794?

The base must be explicitly specified as a named parameter:

sage: RIF('101101', base=2)

45

sage: RIF('+infinity')

[+infinity .. +infinity]

sage: RIF('[1..3]').str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 3.0000000000000000]'

Next we coerce some 2-tuples, which define intervals.

sage: RIF((-1.5, -1.3))

-1.4?

sage: RIF((RDF('-1.5'), RDF('-1.3')))

-1.4?

sage: RIF((1/3,2/3)).str(style='brackets')

'[0.33333333333333331 .. 0.66666666666666675]'

The extra parentheses aren’t needed.

sage: RIF(1/3,2/3).str(style='brackets')

'[0.33333333333333331 .. 0.66666666666666675]'

sage: RIF((1,2)).str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 2.0000000000000000]'

sage: RIF((1r,2r)).str(style='brackets')

'[1.0000000000000000 .. 2.0000000000000000]'

sage: RIF((pi, e)).str(style='brackets')

'[2.7182818284590455 .. 3.1415926535897932]'

Values which can be represented as an exact floating-point number (of the precision of this RealIntervalField) result in a precise interval, where the lower bound is equal to the upper bound (even if they print differently). Other values typically result in an interval where the lower and upper bounds are adjacent floating-point numbers.

sage: def check(x):

... return (x, x.lower() == x.upper())

sage: check(RIF(pi))

(3.141592653589794?, False)

sage: check(RIF(RR(pi)))

(3.1415926535897932?, True)

sage: check(RIF(1.5))

(1.5000000000000000?, True)

sage: check(RIF('1.5'))

(1.5000000000000000?, True)

sage: check(RIF(0.1))

(0.10000000000000001?, True)

sage: check(RIF(1/10))

(0.10000000000000000?, False)

sage: check(RIF('0.1'))

(0.10000000000000000?, False)

Similarly, when specifying both ends of an interval, the lower end is rounded down and the upper end is rounded up.

sage: outward = RIF(1/10, 7/10); outward.str(style='brackets')

'[0.099999999999999991 .. 0.70000000000000007]'

sage: nearest = RIF(RR(1/10), RR(7/10)); nearest.str(style='brackets')

'[0.10000000000000000 .. 0.69999999999999996]'

sage: nearest.lower() - outward.lower()

1.38777878078144e-17

sage: outward.upper() - nearest.upper()

1.11022302462516e-16

Some examples with a real interval field of higher precision:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(100)

sage: R(3)

3

sage: R(R(3))

3

sage: R(pi)

3.14159265358979323846264338328?

sage: R(-2/19)

-0.1052631578947368421052631578948?

sage: R(e,pi).str(style='brackets')

'[2.7182818284590452353602874713512 .. 3.1415926535897932384626433832825]'

TESTS:

sage: RIF._lower_field() is RealField(53, rnd='RNDD')

True

sage: RIF._upper_field() is RealField(53, rnd='RNDU')

True

sage: RIF._middle_field() is RR

True

sage: TestSuite(RIF).run()

Returns 0, since the field of real numbers has characteristic 0.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(10).characteristic()

0

Return complex field of the same precision.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF.complex_field()

Complex Interval Field with 53 bits of precision

Returns the functorial construction of self, namely, completion of

the rational numbers with respect to the prime at  ,

and the note that this is an interval field.

,

and the note that this is an interval field.

Also preserves other information that makes this field unique (e.g. precision, print mode).

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(123)

sage: c, S = R.construction(); S

Rational Field

sage: R == c(S)

True

Returns Euler’s gamma constant to the precision of this field.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(100).euler_constant()

0.577215664901532860606512090083?

Returns True, to signify that elements of this field print without sums, so parenthesis aren’t required, e.g., in coefficients of polynomials.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(10).is_atomic_repr()

True

Returns False, since the field of real numbers is not finite.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RealIntervalField(10).is_finite()

False

Returns log(2) to the precision of this field.

EXAMPLES:

sage: R=RealIntervalField(100)

sage: R.log2()

0.693147180559945309417232121458?

sage: R(2).log()

0.693147180559945309417232121458?

Returns pi to the precision of this field.

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField(100)

sage: R.pi()

3.14159265358979323846264338328?

sage: R.pi().sqrt()/2

0.88622692545275801364908374167?

sage: R = RealIntervalField(150)

sage: R.pi().sqrt()/2

0.886226925452758013649083741670572591398774728?

Returns the precision of this field (in bits).

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF.prec()

53

sage: RealIntervalField(200).prec()

200

Returns a random element of self. Any arguments are passed onto the random element function in real field.

By default, this is uniformly distributed in ![[-1, 1]](../../_images/math/5c3818b9565a33fd3aadba10026d32c5e3eea90f.png) .

.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF.random_element()

-0.30607732607725314?

sage: RIF.random_element()

-0.075929193054320221?

sage: RIF.random_element(-100, 100)

-83.808125490023344?

Set or return the scientific notation printing flag. If this flag is True then real numbers with this space as parent print using scientific notation.

INPUT:

Returns a real interval field to the given precision.

EXAMPLES:

sage: RIF.to_prec(200)

Real Interval Field with 200 bits of precision

sage: RIF.to_prec(20)

Real Interval Field with 20 bits of precision

sage: RIF.to_prec(53) is RIF

True

Return an  -th root of unity in the real field, if one

exists, or raise a ValueError otherwise.

-th root of unity in the real field, if one

exists, or raise a ValueError otherwise.

EXAMPLES:

sage: R = RealIntervalField()

sage: R.zeta()

-1

sage: R.zeta(1)

1

sage: R.zeta(5)

...

ValueError: No 5th root of unity in self