of Integers¶

of Integers¶The class IntegerRing represents the ring

of (arbitrary precision) integers. Each

integer is an instance of the class Integer, which

is defined in a Pyrex extension module that wraps GMP integers (the

mpz_t type in GMP).

of (arbitrary precision) integers. Each

integer is an instance of the class Integer, which

is defined in a Pyrex extension module that wraps GMP integers (the

mpz_t type in GMP).

sage: Z = IntegerRing(); Z

Integer Ring

sage: Z.characteristic()

0

sage: Z.is_field()

False

There is a unique instances of class IntegerRing. To create an Integer, coerce either a Python int, long, or a string. Various other types will also coerce to the integers, when it makes sense.

sage: a = Z(1234); b = Z(5678); print a, b

1234 5678

sage: type(a)

<type 'sage.rings.integer.Integer'>

sage: a + b

6912

sage: Z('94803849083985934859834583945394')

94803849083985934859834583945394

Return the integer ring

EXAMPLE:

sage: IntegerRing()

Integer Ring

sage: ZZ==IntegerRing()

True

Bases: sage.rings.ring.PrincipalIdealDomain

The ring of integers.

In order to introduce the ring  of integers, we

illustrate creation, calling a few functions, and working with its

elements.

of integers, we

illustrate creation, calling a few functions, and working with its

elements.

sage: Z = IntegerRing(); Z

Integer Ring

sage: Z.characteristic()

0

sage: Z.is_field()

False

sage: Z.category()

Category of euclidean domains

sage: Z(2^(2^5) + 1)

4294967297

One can give strings to create integers. Strings starting with 0x are interpreted as hexadecimal, and strings starting with 0 are interpreted as octal:

sage: parent('37')

<type 'str'>

sage: parent(Z('37'))

Integer Ring

sage: Z('0x10')

16

sage: Z('0x1a')

26

sage: Z('020')

16

As an inverse to digits(), lists of digits are accepted, provided that you give a base. The lists are interpreted in little-endian order, so that entry i of the list is the coefficient of base^i:

sage: Z([3, 7], 10)

73

sage: Z([3, 7], 9)

66

sage: Z([], 10)

0

We next illustrate basic arithmetic in  :

:

sage: a = Z(1234); b = Z(5678); print a, b

1234 5678

sage: type(a)

<type 'sage.rings.integer.Integer'>

sage: a + b

6912

sage: b + a

6912

sage: a * b

7006652

sage: b * a

7006652

sage: a - b

-4444

sage: b - a

4444

When we divide to integers using /, the result is automatically coerced to the field of rational numbers, even if the result is an integer.

sage: a / b

617/2839

sage: type(a/b)

<type 'sage.rings.rational.Rational'>

sage: a/a

1

sage: type(a/a)

<type 'sage.rings.rational.Rational'>

For floor division, instead using the // operator:

sage: a // b

0

sage: type(a//b)

<type 'sage.rings.integer.Integer'>

Next we illustrate arithmetic with automatic coercion. The types that coerce are: str, int, long, Integer.

sage: a + 17

1251

sage: a * 374

461516

sage: 374 * a

461516

sage: a/19

1234/19

sage: 0 + Z(-64)

-64

Integers can be coerced:

sage: a = Z(-64)

sage: int(a)

-64

We can create integers from several types of objects.

sage: ZZ(17/1)

17

sage: ZZ(Mod(19,23))

19

sage: ZZ(2 + 3*5 + O(5^3))

17

Return the absolute degree of the integers, which is 1

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.absolute_degree()

1

Return the characteristic of the integers, which is 0

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.characteristic()

0

Returns the completion of Z at p.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.completion(infinity, 53)

Real Field with 53 bits of precision

sage: ZZ.completion(5, 15, {'print_mode': 'bars'})

5-adic Ring with capped relative precision 15

Return the degree of the integers, which is 1

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.degree()

1

Returns the order in the number field defined by poly generated (as a ring) by a root of poly.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.extension(x^2-5, 'a')

Order in Number Field in a with defining polynomial x^2 - 5

sage: ZZ.extension([x^2 + 1, x^2 + 2], 'a,b')

Relative Order in Number Field in a with defining polynomial x^2 + 1 over its base field

Returns the field of rational numbers - the fraction field of the integers.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.fraction_field()

Rational Field

sage: ZZ.fraction_field() == QQ

True

Returns the additive generator of the integers, which is 1.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.gen()

1

sage: type(ZZ.gen())

<type 'sage.rings.integer.Integer'>

Returns the tuple (1,) containing a single element, the additive generator of the integers, which is 1.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.gens(); ZZ.gens()[0]

(1,)

1

sage: type(ZZ.gens()[0])

<type 'sage.rings.integer.Integer'>

Return True, since elements of the integers do not have to be printed with parentheses around them, when they are coefficients, e.g., in a polynomial.

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.is_atomic_repr()

True

Return False - the integers are not a field.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.is_field()

False

Return False - the integers are an infinite ring.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.is_finite()

False

Returns that the integer ring is, in fact, an integrally closed ring.

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.is_integrally_closed()

True

Return True - the integers are a Noetherian ring.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.is_noetherian()

True

Return True if ZZ is a subring of other in a natural way.

Every ring of characteristic 0 contains ZZ as a subring.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.is_subring(QQ)

True

Return the Krull dimension of the integers, which is 1.

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.krull_dimension()

1

Returns the number of additive generators of the ring, which is 1.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.ngens()

1

sage: len(ZZ.gens())

1

Return the order (cardinality) of the integers, which is +Infinity.

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.order()

+Infinity

Returns an integer of degree 1 for the Euclidean property of ZZ, namely 1.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.parameter()

1

Return the quotient of  by the ideal

by the ideal

or integer

or integer  .

.

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.quo(6*ZZ)

Ring of integers modulo 6

sage: ZZ.quo(0*ZZ)

Integer Ring

sage: ZZ.quo(3)

Ring of integers modulo 3

sage: ZZ.quo(3*QQ)

...

TypeError: I must be an ideal of ZZ

Return a random integer.

- ZZ.random_element()

- return an integer using the default distribution described below

- ZZ.random_element(n)

- return an integer uniformly distributed between 0 and n-1, inclusive.

- ZZ.random_element(min, max)

- return an integer uniformly distributed between min and max-1, inclusive.

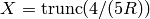

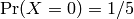

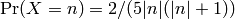

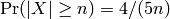

The default distribution for ZZ.random_element() is based on

, where

, where  is a random

variable uniformly distributed between -1 and 1. This gives

is a random

variable uniformly distributed between -1 and 1. This gives

, and

, and

for

for

. Most of the samples will be small; -1, 0, and 1

occur with probability 1/5 each. But we also have a small but

non-negligible proportion of “outliers”;

. Most of the samples will be small; -1, 0, and 1

occur with probability 1/5 each. But we also have a small but

non-negligible proportion of “outliers”;

, so for instance, we

expect that

, so for instance, we

expect that  on one in 1250 samples.

on one in 1250 samples.

We actually use an easy-to-compute truncation of the above

distribution; the probabilities given above hold fairly well up to

about  , but around

, but around  some

values will never be returned at all, and we will never return

anything greater than

some

values will never be returned at all, and we will never return

anything greater than  .

.

EXAMPLES:

The default distribution is on average 50%

sage: [ZZ.random_element() for _ in range(10)]

[-8, 2, 0, 0, 1, -1, 2, 1, -95, -1]

The default uniform distribution is integers between -2 and 2 inclusive:

sage: [ZZ.random_element(distribution="uniform") \

for _ in range(10)]

[2, -2, 2, -2, -1, 1, -1, 2, 1, 0]

If a range is given, the distribution is uniform in that range:

sage: ZZ.random_element(-10,10)

-5

sage: ZZ.random_element(10)

7

sage: ZZ.random_element(10^50)

62498971546782665598023036522931234266801185891699

sage: [ZZ.random_element(5) for _ in range(10)]

[1, 3, 4, 0, 3, 4, 0, 3, 0, 1]

Notice that the right endpoint is not included:

sage: [ZZ.random_element(-2,2) for _ in range(10)]

[-1, -2, 0, -2, 1, -1, -1, -2, -2, 1]

We compute a histogram over 1000 samples of the default distribution:

sage: from collections import defaultdict

sage: d = defaultdict(lambda: 0)

sage: for _ in range(1000):

... samp = ZZ.random_element()

... d[samp] = d[samp] + 1

sage: sorted(d.items())

[(-1026, 1), (-248, 1), (-145, 1), (-81, 1), (-80, 1), (-79, 1), (-75, 1), (-69, 1), (-68, 1), (-63, 2), (-61, 1), (-57, 1), (-50, 1), (-37, 1), (-35, 1), (-33, 1), (-29, 2), (-27, 2), (-25, 1), (-23, 2), (-22, 2), (-20, 1), (-19, 1), (-18, 1), (-16, 4), (-15, 3), (-14, 1), (-13, 2), (-12, 2), (-11, 2), (-10, 7), (-9, 3), (-8, 3), (-7, 7), (-6, 8), (-5, 13), (-4, 24), (-3, 34), (-2, 75), (-1, 207), (0, 209), (1, 189), (2, 64), (3, 35), (4, 13), (5, 11), (6, 10), (7, 4), (8, 4), (10, 1), (11, 1), (12, 1), (13, 1), (14, 1), (16, 3), (18, 1), (19, 1), (26, 2), (27, 1), (28, 1), (29, 1), (30, 1), (32, 1), (33, 2), (35, 1), (37, 1), (39, 1), (41, 1), (42, 1), (52, 1), (91, 1), (94, 1), (106, 1), (111, 1), (113, 2), (132, 1), (134, 1), (232, 1), (240, 1), (2133, 1), (3636, 1)]

Optimized range function for Sage integer.

AUTHORS:

EXAMPLES:

sage: ZZ.range(10)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

sage: ZZ.range(-5,5)

[-5, -4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

sage: ZZ.range(0,50,5)

[0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45]

sage: ZZ.range(0,50,-5)

[]

sage: ZZ.range(50,0,-5)

[50, 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 5]

sage: ZZ.range(50,0,5)

[]

sage: ZZ.range(50,-1,-5)

[50, 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 5, 0]

It uses different code if the step doesn’t fit in a long:

sage: ZZ.range(0,2^83,2^80)

[0, 1208925819614629174706176, 2417851639229258349412352, 3626777458843887524118528, 4835703278458516698824704, 6044629098073145873530880, 7253554917687775048237056, 8462480737302404222943232]

Make sure #8818 is fixed:

sage: ZZ.range(1r, 10r)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Return the residue field of the integers modulo the given prime, ie

.

.

INPUT:

OUTPUT: The residue field at this prime.

EXAMPLES:

sage: F = ZZ.residue_field(61); F

Residue field of Integers modulo 61

sage: pi = F.reduction_map(); pi

Partially defined reduction map from Rational Field to Residue field of Integers modulo 61

sage: pi(123/234)

6

sage: pi(1/61)

...

ZeroDivisionError: Cannot reduce rational 1/61 modulo 61: it has negative valuation

sage: lift = F.lift_map(); lift

Lifting map from Residue field of Integers modulo 61 to Rational Field

sage: lift(F(12345/67890))

33

sage: (12345/67890) % 61

33

Construction can be from a prime ideal instead of a prime:

sage: ZZ.residue_field(ZZ.ideal(97))

Residue field of Integers modulo 97

TESTS:

sage: ZZ.residue_field(ZZ.ideal(96))

...

TypeError: Principal ideal (96) of Integer Ring is not prime

sage: ZZ.residue_field(96)

...

TypeError: 96 is not prime

Return a primitive n’th root of unity in the integers, or raise an error if none exists

INPUT:

OUTPUT: an n’th root of unity in ZZ

EXAMPLE:

sage: ZZ.zeta()

-1

sage: ZZ.zeta(1)

1

sage: ZZ.zeta(3)

...

ValueError: no nth root of unity in integer ring

sage: ZZ.zeta(0)

...

ValueError: n must be positive in zeta()

Compute and return a Chinese Remainder Theorem basis for the list X of coprime integers.

INPUT:

OUTPUT:

The E[i] have the property that if A is a list of objects, e.g., integers, vectors, matrices, etc., where A[i] is moduli X[i], then a CRT lift of A is simply

sum E[i] * A[i].

ALGORITHM: To compute E[i], compute integers s and t such that

s * X[i] + t * (prod over i!=j of X[j]) = 1. (*)

Then E[i] = t * (prod over i!=j of X[j]). Notice that equation (*) implies that E[i] is congruent to 1 modulo X[i] and to 0 modulo the other X[j] for j!=i.

COMPLEXITY: We compute len(X) extended GCD’s.

EXAMPLES:

sage: X = [11,20,31,51]

sage: E = crt_basis([11,20,31,51])

sage: E[0]%X[0]; E[1]%X[0]; E[2]%X[0]; E[3]%X[0]

1

0

0

0

sage: E[0]%X[1]; E[1]%X[1]; E[2]%X[1]; E[3]%X[1]

0

1

0

0

sage: E[0]%X[2]; E[1]%X[2]; E[2]%X[2]; E[3]%X[2]

0

0

1

0

sage: E[0]%X[3]; E[1]%X[3]; E[2]%X[3]; E[3]%X[3]

0

0

0

1

Return the factorization of the positive integer  as a

sorted list of tuples

as a

sorted list of tuples  such that

such that

.

.

For further documentation see sage.rings.arith.factor()

EXAMPLE:

sage: sage.rings.integer_ring.factor(420)

2^2 * 3 * 5 * 7

Internal function: returns true iff x is the ring ZZ of integers

EXAMPLES:

sage: from sage.rings.integer_ring import is_IntegerRing

sage: is_IntegerRing(ZZ)

True

sage: is_IntegerRing(QQ)

False

sage: is_IntegerRing(parent(3))

True

sage: is_IntegerRing(parent(1/3))

False