This is a tour of Sage that closely follows the tour of Mathematica that is at the beginning of the Mathematica Book.

The Sage command line has a sage: prompt; you do not have to add it. If you use the Sage notebook, then put everything after the sage: prompt in an input cell, and press shift-enter to compute the corresponding output.

sage: 3 + 5

8

The caret symbol means “raise to a power”.

sage: 57.1 ^ 100

4.60904368661396e175

We compute the inverse of a  matrix in Sage.

matrix in Sage.

sage: matrix([[1,2], [3,4]])^(-1)

[ -2 1]

[ 3/2 -1/2]

Here we integrate a simple function.

sage: x = var('x') # create a symbolic variable

sage: integrate(sqrt(x)*sqrt(1+x), x)

1/4*((x + 1)^(3/2)/x^(3/2) + sqrt(x + 1)/sqrt(x))/((x + 1)^2/x^2 - 2*(x + 1)/x + 1) + 1/8*log(sqrt(x + 1)/sqrt(x) - 1) - 1/8*log(sqrt(x + 1)/sqrt(x) + 1)

This asks Sage to solve a quadratic equation. The symbol == represents equality in Sage.

sage: a = var('a')

sage: S = solve(x^2 + x == a, x); S

[x == -1/2*sqrt(4*a + 1) - 1/2, x == 1/2*sqrt(4*a + 1) - 1/2]

The result is a list of equalities.

sage: S[0].rhs()

-1/2*sqrt(4*a + 1) - 1/2

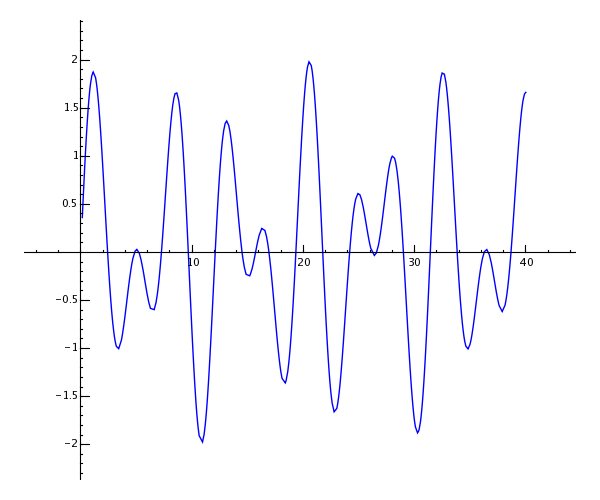

sage: show(plot(sin(x) + sin(1.6*x), 0, 40))

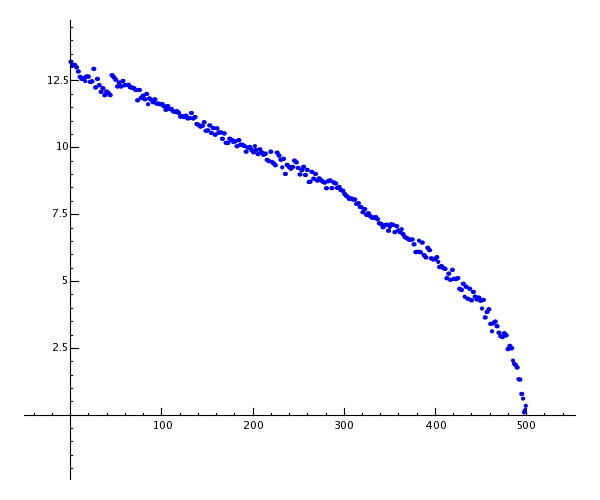

First we create a  matrix of random

numbers.

matrix of random

numbers.

sage: m = random_matrix(RDF,500)

It takes Sage a few seconds to compute the eigenvalues of the matrix and plot them.

sage: e = m.eigenvalues() #about 2 seconds

sage: w = [(i, abs(e[i])) for i in range(len(e))]

sage: show(points(w))

Thanks to the GNU Multiprecision Library (GMP), Sage can handle very large numbers, even numbers with millions or billions of digits.

sage: factorial(100)

93326215443944152681699238856266700490715968264381621468592963895217599993229915608941463976156518286253697920827223758251185210916864000000000000000000000000

sage: n = factorial(1000000) #about 2.5 seconds

This computes at least 100 digits of  .

.

sage: N(pi, digits=100)

3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197169399375105820974944592307816406286208998628034825342117068

This asks Sage to factor a polynomial in two variables.

sage: R.<x,y> = QQ[]

sage: F = factor(x^99 + y^99)

sage: F

(x + y) * (x^2 - x*y + y^2) * (x^6 - x^3*y^3 + y^6) *

(x^10 - x^9*y + x^8*y^2 - x^7*y^3 + x^6*y^4 - x^5*y^5 +

x^4*y^6 - x^3*y^7 + x^2*y^8 - x*y^9 + y^10) *

(x^20 + x^19*y - x^17*y^3 - x^16*y^4 + x^14*y^6 + x^13*y^7 -

x^11*y^9 - x^10*y^10 - x^9*y^11 + x^7*y^13 + x^6*y^14 -

x^4*y^16 - x^3*y^17 + x*y^19 + y^20) * (x^60 + x^57*y^3 -

x^51*y^9 - x^48*y^12 + x^42*y^18 + x^39*y^21 - x^33*y^27 -

x^30*y^30 - x^27*y^33 + x^21*y^39 + x^18*y^42 - x^12*y^48 -

x^9*y^51 + x^3*y^57 + y^60)

sage: F.expand()

x^99 + y^99

Sage takes just under 5 seconds to compute the numbers of ways to partition one hundred million as a sum of positive integers.

sage: z = Partitions(10^8).cardinality() #about 4.5 seconds

sage: str(z)[:40]

'1760517045946249141360373894679135204009'

Whenever you use Sage you are accessing one of the world’s largest collections of open source computational algorithms.